Art as Resistance: Victor Jara and the Nueva Cancion Movement by Raul Alonzo

As for now, this is the broadcast network of the Armed Forces – Santiago, September 11th, 1973. Considering, first: the terrible economic, social and moral crisis destroying the country; secondly the government’s failure to adopt measures to prevent the growth of chaos; the Armed Forces and Police declare that the President must immediately transfer his powers to the Armed Forces and Police of Chile.

Signed,

Augusto Pinochet Ugarte

Commander-in-Chief of the Army

On the day the Armed Forces of Chile staged a violent coup to overthrow the democratically elected president Salvador Allende, radio broadcasts across the country fell silent. Those taken over by the military were left on either a loop of martial music, military orders or broadcasts declaring the aims of the coup. By the end of the day, Allende would be dead and power would be concentrated in a military dictatorship composed of the heads of the Police, Navy and Air Force with General Augusto Pinochet, Commander of the Army, overseeing the operations.

As tanks and soldiers patrolled the streets and a curfew was imposed, folk singer Victor Jara tried to raise the hopes of those around him.

A teacher at the Technical University in the capitol, Jara sang to ease the minds of the students and faculty who had seen the tanks surrounding the campus and could hear the machine gun fire that pierced through the night.

He would sing the songs they had known when the music of Nueva Cancion (New Song) could be heard on the radios of Santiago.

Nueva Cancion

Nueva Cancion is a genre of music that emerged from Chile in the 1960s, drawing largely from the traditional music of the Andes as well as other Latin American song forms and styles, such as cueca. One of the defining characteristics of the movement were the socially-conscious lyrics, influenced greatly by working class issues, human rights, imperialism and poverty.

Many Nueva Cancion musicians, including Jara, who was a member of the Communist Party, would lend their voices to the presidential campaign of Salvador Allende – a Marxist and candidate of the Unidad Popular coalition of leftist parties. Along with Inti-Illimani, Jara composed “Venceremos,” the official song of the Allende campaign. The movement would also birth the song “El Pueblo Unido, Jamas Sera Vencido!,” a song that is still utilized by social movements internationally. It was this sort of commitment to social change that led American musicians, such as Phil Ochs, to regard artists such as Jara as “the real deal.”

Indeed, the American protest song movement had at that point become widely commercialized and stripped of its radical edge. As Jara said of the American scene:

“US imperialism understands very well the magic of communication through music and persists in filling our young people with all sorts of commercial tripe. With professional expertise they have taken certain measures: first, the commercialization of the so-called ‘protest music’; second, the creation of ‘idols’ of protest music who obey the same rules and suffer from the same constraints as the other idols of the consumer music industry – they last a little while and then disappear. Meanwhile they are useful in neutralizing the innate spirit of rebellion of young people.”

For Jara, with musical roots percolating through an indigenous foundation, Nueva Cancion provided an alternative to the commercialized “protest music” of the United States.

“The term ‘protest song’ is no longer valid because it is ambiguous and has been misused. I prefer the term ‘revolutionary song.'”

Apagon Cultural

“The military junta assumes the task of reconstructing the country morally, institutionally and materially. The supreme task exists of changing the mentality of Chileans.”

Allende would go on to win the 1970 presidential election, a victory that he hoped to use to alleviate the vast poverty of the country, as well as take steps to nationalize industries so that resources could be used to enrich Chile, rather than foreign business interests.

The election, however, would arouse the concern of one of the more hegemonic business interests: the United States.

As President Nixon vowed to “make the [Chilean] economy scream,” right wing military forces in Chile were in the process of determining how to undermine the new administration. While the U.S. has not been found to be directly involved in the coup, the support for the forces behind it and the subsequent engineering of the neoliberal economic model the military junta imposed hardly absolves the country. As Henry Kissinger noted after Allende’s election:

“I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go Marxist due to the irresponsibility of its people. The issues are much too important for the Chilean voters to be left to decide for themselves.”

As the junta consolidated its power, members of the opposition faced violent repression. Lists of suspected dissidents or subversives were summoned for trial over the military radio as death squads, such as the Caravan of Death, scoured the country – rounding up and executing suspects. In total, 3,197 citizens were murdered or “disappeared” in this period with thousands more subjected to torture, forced exile, or arbitrary incarceration. All institutions, including the universities and Congress, were taken over or suspended by the regime. Political repression was rampant and there was a genuine fear in receiving a knock at the door in the late hours of the night.

Chilean essayist and critic, Soledad Bianchi, has referred to the period of military rule under Pinochet as one of apagon cultural or cultural blackout. As in other Latin American countries that fell to dictatorships during this period, popular musicians faced persecution.

Nueva Cancion groups that were touring abroad at the time of the coup, such as Inti-Illimani and Quilapayun, were forced to remain in exile. The government referred to Andean music as “subversive” and banned traditional instruments such as the quena and charango. Nueva Cancion albums were burned along with the films and literature deemed to be a threat to the power of the new regime.

In the later years of the dictatorship, Nueva Cancion would take on a more diminished form, now known as Canto Nuevo, with socially-conscious lyrics referenced only through metaphor and performances generally taking place in the underground cafe’s of the opposition.

Estadio Chile

Fear, sensation, bombardment and powerlessness. The walls of the Technical University crumbled beneath the big guns of the military’s tanks. Soldiers entered the buildings, whipping up a herd of terrified faces before them with their rifle butts and forcing them to lie on the pavement – hands on their heads.

After an hour on the ground, the soldiers marched them to the Estadio Chile, a stadium that was serving as a massive holding area for political prisoners. The stadium had also been a venue for Nueva Cancion artists, including Jara, just months ago. It was here that Jara was recognized by one of the non-commissioned officers. The officer knocked him to the ground, proceeding to violently kick him in the stomach and ribs.

He was cordoned off to a part of the stadium reserved for high profile prisoners. Enduring further beatings at the hands of soldiers and officers over the next few days, Jara finally had an opportunity to record what he had seen when a friend was able to give him some paper and a pencil. With this he would pen his final poem, unnamed but commonly referred to “Estadio Chile.”

There are five thousand of us here

in this small part of the city.

We are five thousand.

I wonder how many we are in all

in the cities and in the whole country?

As the soldiers came for Jara, he slipped the poem to a friend who hid it in his sock. The hands of Victor Jara were smashed – his bones, broken on the soldier’s rifles, never to strum the hopeful songs that were being purged from the people’s poet. Soldiers who mocked and jeered him to play threw his guitar to him. In stark defiance, Jara began to sing a few lines from “Venceremos”:

We shall prevail, we shall prevail…

It would not be until the morning of Sunday, September the 16th, that the body of Victor Jara was found among six others – lying in an orderly row in the neighborhood of one of the working class districts. His face was beaten and bloodied beyond recognition, and a violent barrage of 44 bullets riddled his corpse, like craters.

The legacy of Victor Jara is not so much simply the tragic contrast of his message of peace and humanity with the brutal way he was murdered. His music may have died with him if it had not been for his wife, Joan, who smuggled the recordings out of the country. The stadium he was murdered in has been renamed the Estadio Victor Jara, and towards the end of last year eight retired army officers were charged with his murder. Pedro Barrientos, one of the officers responsible for Jara’s death, lives in Florida currently evading trial.

Jara’s story also stands as an example of the role culture and the arts can play in revolutionary movements – and the threat they present to authoritarian regimes, so much so as to provoke severe repression when power is consolidated.

As with all musicians of the past who could be called truly revolutionary, Jara lives on in his music. The tender, sometimes haunting, sincerity Jara sang with was fueled by his love for people and his confidence in the future of humanity.

In many ways, his vision never died. Today, Chile has not only seen the resurgence of a popular student movement challenging neoliberalism, but South America as a whole has seen a region-wide shift to reclaim the legacies established before the dark years of colonialism, imperialism and military dictatorship gripped the land.

“I may die as one, but I will come back in millions.”

The determination of the peoples of Latin America to forge their own future is the foundation on which the words of Victor Jara will continue to be sung – whistling on the winds blowing down from the Andes, carrying with them the spirits of the past and the visions of the future.

Strike #6 IS NOW AVAILABLE!

Just a reminder for folks wanting to receive a copy of Strike #6 by mail: Please be sure we have your address. Each copy comes with a Strike Magazine button. PM us or send us an email to StrikeMagazineEditors@yahoo.com

Steal Away: An Interview with Craig Ross, Creator of the Comic Book “Steal Away: The Visions of Nat Turner”

Blast Furnace: The Origins and Ideas of Third Cinema

Poetas De La Frontera: A Conversation with Rio Grande Valley Poets, Isaac Chavarria and Chrisopher Carmona

Sounds of Strike: What We’re Listening To

And a selection of international poetry!

Dear Mr. President

By Casey Rocheteau

for Abdulrahman al-Aulaqi

Sure, nobody’s perfect.

You inherited the cross from

the last guy who dipped it

in lead.

Nobody’s perfect, but nearly none of us

will wield your arsenal, and no one

but you makes the promises you will break.

Spit the name Guantanamo out

as if it were a loose tooth and

then tell me you were a good man once.

Your ambition belies bloodsport, big man.

You talk a good game, Overt Ops.

My street runneth over with a thousand

ornery beasts, necks angled to the dry earth.

You send them to greet anyone

who might know a word of conversation

about laying siege to the fortress.

You send them daily, firing reckless

upon children while you sit in your study,

mourning the dull glint of your peace prize.

You were not their first

master, just the first most like us

before you shovelled the money

back into the country clubs

before you alley-ooped the

Patriot Act, Air President.

Take your transparency charade

to the weeping sisters, and prove

to them your earnesty without making

a speech, without telling them, Look

You are still so far from being like us,

because you haven’t changed your mind

about who we are to you.

We, the united target demographic,

were persuaded in a process of dissolving.

You were not the slogan, nor the idol.

But we did not forget

that hope was the password,

what we want does not evaporate

so we became rain upon your parks.

Now I know not to speak for those

Who chant the name of a murderer

despite their innocence. Trust that

You and I are different because

I know

There will be another flood.

Always has been.

Casey Rocheteau began performing poetry at Hampshire College in 2003. She performs throughout the country, at venues such as the Green Mill, The Cantab Lounge, and Portland Poetry Slam. She has lead a variety of writing and performance workshops for adults and students from middle school to college age. She’s released two albums on the Whitehaus Family Record: Pump Your Concrete in 2008 and Chiaroscuro in 2011. Her most recent book, Knocked Up On Yes was released on Sargent Press in 2012. Recently her work has appeared in Amethyst Arsenic and Side B Magazine. Casey was a member of the 2012 Providence Slam Team.

The Fix: Strike Magazine’s Weekly Round Up 10/31/13

Follow the links to see for yourself!

Follow the links to see for yourself!

Beatriz: I got a kick out of this, the first audio digital recording synced with a movie. It was a Warner Bros experiment that spearheaded the new, expensive movement and bumped silent movie stars into depression and drug dependencies. Its amusing to imagine people’s reaction to the deceiving introduction to the movie, setting it up as just another silent film. This movie faces controversy to this day because the main character performs in blackface regularly throughout. One of the original posters featured him wearing the blackface, even. Along with The Birth of a Nation, two of the US’ biggest contributions to the art of cinema also serve as treatments to its incredibly racist past.

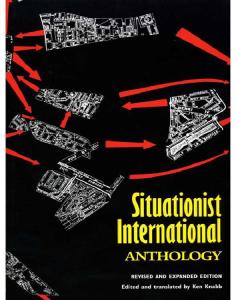

Raul: I’ve only a vague conception of who the Situationists were and what they were about, so when libcom.org posted this anthology the other day for folks to download I immediately went for it. I’ve only made a little headway so far but already some of the ideas I’ve read range from the utterly, and effectively, subversive to almost tongue-in-cheek in their blunt surmises of how to overturn prevailing notions of culture and the status quo. With a legacy that influenced punk music, culture jamming and the May 1968 student movement in France that almost resulted in a full scale revolution, I can say that I think I will enjoy tackling this tome. Give it a download and join me.

Raul: I’ve only a vague conception of who the Situationists were and what they were about, so when libcom.org posted this anthology the other day for folks to download I immediately went for it. I’ve only made a little headway so far but already some of the ideas I’ve read range from the utterly, and effectively, subversive to almost tongue-in-cheek in their blunt surmises of how to overturn prevailing notions of culture and the status quo. With a legacy that influenced punk music, culture jamming and the May 1968 student movement in France that almost resulted in a full scale revolution, I can say that I think I will enjoy tackling this tome. Give it a download and join me.

Mike: Ever wonder how socialists view the horror film genre? I couldn’t sum it up any better than this from www.socialistworker.org: “As it so happens, there are plenty of horror movies that eschew the sexist and racist detritus that has given the genre much of its bad reputation. In fact, there are even a small number of these films that prominently feature an anti-capitalist monologue or build upon an unmistakably subversive political subtext. The fact that the decapitated head rolls left on occasion should be enough to allow socialists to bury our guilt about indulging the desire to scare ourselves silly this Halloween season–but to leave it at that would be to forget our Trotsky.”

Mike: Ever wonder how socialists view the horror film genre? I couldn’t sum it up any better than this from www.socialistworker.org: “As it so happens, there are plenty of horror movies that eschew the sexist and racist detritus that has given the genre much of its bad reputation. In fact, there are even a small number of these films that prominently feature an anti-capitalist monologue or build upon an unmistakably subversive political subtext. The fact that the decapitated head rolls left on occasion should be enough to allow socialists to bury our guilt about indulging the desire to scare ourselves silly this Halloween season–but to leave it at that would be to forget our Trotsky.”

Betty: Check out this collection of recreated movie art posters. Love the fact that they aren’t just actor screen shots. The “art” in movie poster design today has lost the ability of painting what the feeling of the film should deliver to its audience. This has triggered American writer Matthew Chojnacki to bring back the idea of how the film art posters before use to look like – breathing with pure art and creative concept.

Betty: Check out this collection of recreated movie art posters. Love the fact that they aren’t just actor screen shots. The “art” in movie poster design today has lost the ability of painting what the feeling of the film should deliver to its audience. This has triggered American writer Matthew Chojnacki to bring back the idea of how the film art posters before use to look like – breathing with pure art and creative concept.

Dia de los Muertos (or How I Learned About Life, Death and The Spanish Invasion by Building An Altar)

Words and Photos by Stella Becerril

Words and Photos by Stella Becerril

As with much of Mexico’s customs, holidays, and identity, El Dia de Los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, is a mix of pre-colonial indigenous rituals and post-colonial Catholic rites. The latter bit however, was brutally imposed on the indigenous people of Mexico by the Spanish Crown and Catholic Church. Originally an indigenous pagan holiday, El Dia de Los Muertos was a celebration of the life and death of family and friends who had embarked on their journey from this life to the next. Unlike the colonizers who viewed death as the end of life and feared it, Mezo-Americans embraced and respected death and the duality of one’s existence. This celebration the Catholic Church found distasteful and savage and moved to eradicate it, no matter the cost. So relentless were the Crown and the Church that in the first 100 years of the Spanish invasion 96 percent of Mexico’s First Peoples were murdered, leaving the indigenous population at only 1 million by 1600 from 25 million in 1491. But even genocide wasn’t enough kill a tradition that went back 3,000 years. Realizing this, the Church decided to employ a different, less genocidal strategy and make the indigenous people’s celebration more Christian by moving it from August to November and condensing what was a month long celebration down to two days so that it would coincide with the Church’s established All Saints’ and All Souls’ Days.

- Altar with offering for Bertin Ventura, October 28th, 2012

(photograph of Bertin with his sisters and his mom, circa 1979; post card of “lady death”)

(perforated paper decorations, Mexican marigolds, Virgin Mary candle, Mexican beer Victoria, chicken in green sauce tamale, sweet bread for the dead, sugar skull, assortment of Mexican candy, hot cornmeal and chocolate breakfast beverage, photograph in clay frame.)

Today, El Dia de Los Muertos is still wildly celebrated in the central and southern parts of Mexico and recognized as a national holiday in all 31 states of the Union. While details and rituals vary from state to state, it is customary to build altars in memory and celebration of the deceased, set up Hanal Pixan -Nahuatl for offerings of food for the souls- and visit their loved one’s grave sites to spend the day cleaning and decorating it and sharing anecdotes to remember shared times. However, because so much of our cultural and spiritual beliefs and behaviors are a complex marriage of two different approaches to life and death, the dualities and contradictions abound. While Dia de Los Muertos is largely regarded as a celebration, it is likewise a sad and mournful time for those left behind on earth. And even though Mexico’s First People’s put up tremendous fights for centuries following Cortez’s debut in the Americas, Catholicism was largely successful in it’s take-over of Mexico, and with that came fear, guilt, and regret.

(perforated paper decorations, Mexican marigolds.)

It seems nearly every aspect of our lives as Mexicans- or Mexican-American in my case- is a great balancing act fraught with contradictions and dualities. It’s simultaneously celebrating and fearing death; longing for eternal-life in heaven but never being quite ready to leave this place. For me it is abstaining from organized religion but never failing to drop-off red roses to La Virgencita de Güadalupe on her birthday the 12th of December; being relatively successful at living bi-culturally and yet waking up somedays with an unexplainable anxiety until I realize it’s that familiar feeling of not knowing where the f*ck I belong. It’s proudly announcing my departure from the Catholic church at seventeen and then running all over town trying to find cempasúchitl (Mexican marigolds) for my uncle’s altar. It’s being that nerdy Mexican girl who never quite fit in with the other Mexican kids on her block or with the white kids in her dorm. In a word, it’s limbo.

(Mexican beer Victoria, chicken in green sauce tamale, sugar skull, hot chocolate cornmeal breakfast beverage, photograph in clay frame.)

But it’s also having a wealth of culture and experiencing life in a unique (albeit sometimes rather confusing) way. Whatever it is, there’s a reason why it’s still such an important and relevant holiday and why despite growing up in Chicago and not Mexico, the ties that bind are still strong and ever presenta.

* * *

Crystal Stella Becerril is a Mexican-American community organizer, activist, and photographer currently living in Chicago. Her work has appeared in Red Wedge Magazine and she has contributed written work to SocialistWorker.org. Stella studied photography at The Fashion Institute of Technology in New York City and in 2007 her photography was part of a group exhibition at Caza Aztlan Community Center in Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood. She is currently a student at Harold Washington College where she is majoring in History and Philosophy, as well as a community organizer with Voices of Youth in Chicago Education and the Chicago Teachers Solidarity Campaign. She is also a member of the International Socialist Organization.

Sunday

By Sabrina Hinojosa

If only you could see what I see.

Rub it left handed as you write down the page.

Dear Stranger,

Do not waste your lead on me.

Short stories hidden in milk crates

I’m too afraid to throw away.

Dear Lover,

Let ginger candy line my pockets and burn my tongue

Leave my head spinning loud with fairy-tail stories

Rest your tired lips on me.

Heavy.

Do you think of me?

Stereo speakers fastened on

Lazy church trees near your mother’s house.

White picket fences.

Laugh lines.

You were waiting in the bathtub

I should’ve known better than to try and fit myself between you and the water.

Lizards

are hiding under the concrete

Mouth gaping.

Backward sigh.

I woke up on a tear-smeared box spring.

I cried out all the good parts of me.

Dear uncertainty.

I see you’ve made it into the New Year and I guess

I am glad to see familiar face butOnly If you could see how I see.

Fireworks on rooftops when you were still foreign on my tongue

Hands always too large to fit in your pockets

Dear stranger,

Forget me.

Sunday.

Sabrina Hinojosa is an artist/poet in Corpus Christi. Her poetry has appeared in Issue 3 of VOLUME and in Red Wedge Magazine. She designed and printed the first 70 covers of Strike #1 and #3. She is a regular contributor to Ballabajoomba Poetry Slam. She is one of the founders of Strike Magazine and served as an editor for the first three issues.

Toward a Holistic Revolutionary Critique of Art

By Bill Crane

China Miéville’s talk on “Guilty Pleasures: Art and Politics,” delivered at Socialism 2012, points socialists in some interesting directions regarding our critique of art. As there have been some interesting arguments on Facebook recently that I’ve participated in – particularly around Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained, but also things like Homeland which I’ve written lengthy critiques of before – I thought now would be a good time to remind everyone, including myself, of the outlines of China’s critique.

China says that one axis of our appreciation of art (for which term, let’s include every cultural product regardless of medium or quality, just for the sake of utility) is the political worldview a certain piece of art has underlying it. As socialists, we are particularly sensitive to this category for obvious reasons. We know, for instance, that art is never politically value-neutral in class society as it can reinforce patterns of class, gender or racial/national domination. In capitalist society, most of the assumptions of artists as a special breed of intellectuals have this effect on their work.

At the same time, however, a piece of art can also propose a politics of liberation in either a broad or narrow sense. Most art doesn’t lie entirely on one side or another of this axis as it can lie somewhere in between based on countervailing pressures of the official ideologies Gramscian “common sense”, and the equally common notions the oppressed or exploited have pointing toward their liberation.

It is common for socialists to recognize that a particular piece of art embeds the politics of oppression in one way or another. There are two typical responses to this.

The first is we can swear off any art that does this, condemn it and refuse to appreciate whatever relative merits it may have. Logically, this position tends to reduce itself to absurdity. I have seen some leftists write that they refuse to watch The Wire because the worldview it promotes is based on a strange breed of Fabianism. This particular breed believes structures of domination, such as the police department, can be reformed with the right people put in charge.

As a result, I think that more often than not this reductive and agitational position is only in very rare cases completely consistent. Because all art in class society, or nearly all art, reflects the influence of systems of domination, to embrace it completely means we wouldn’t ever be able to enjoy anything that doesn’t spring fully-formed from the mind of a revolutionary socialist.

This means concretely, I think, that people who embrace this position are highly selective about where they apply it. The consequences of this can look somewhat bizarre. In the past couple of months I heard a person condemn the film Lincoln because it doesn’t include any black characters. In the next breath, the same person also claims Django Unchained as an anti-racist masterpiece despite the fact that it reduces the talented tenth to the talented ten millionth in the case of the title character; the only other options for slaves laid out were to be completely passive or to actively collaborate with the slaveowners, as in the case of Samuel Jackson’s character.

I say this without accusing anyone in particular because my appreciation of art has been equally deterministic at times. Well after I had transitioned from sci-fi and fantasy geek to revolutionary socialist, I looked back on my youthful infatuation with the work of Tolkien as a particularly regrettable part of my past. The homage to feudal, courtly values paid in every page of his work kept me from seeing the reasons why I’d once appreciated the professor; his keen sense of adventure, his wonderful devotion to world-building being rightly so influential, and romance and myth have made him a hero to generations. It was only after reading pieces by China and John Molyneux that I was able to arrive at a nuanced appreciation for The Lord of the Rings, long-cherished books and movies that I had rejected in the past.

So what I’m saying in other words is that a perspective that uses the axis of “progressive/reactionary” as its main determinant is more often than not applied incredibly selectively. This works both ways, jumping from politics to quality and from quality to politics. We might assume a work is bad because we find its political worldview distasteful, as in the example I gave of my changing appraisal of Tolkien.

I have had less success thinking of an example of the reverse, since fiction with an agitational purpose is usually only interesting in how it fails. I have never been particularly fond of Upton Sinclair, the socialist author most famous for The Jungle. As someone smarter than me once said, allegorical fiction (which includes agitational fiction) is hard to take seriously because even its own characters realize that what they’re doing isn’t real. Of course, this only really applies in fiction. I don’t think that poetry, theater, music, etc., are forced to abide by the same limits.

So if we don’t like a film or a book, this may have a conditioning effect on how we see it politically – it will probably be negative. Similarly, the reverse is true: art we do like can be discovered to have good politics on a somewhat shaky basis.

An example: I really enjoy Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy. I think the books are very entertaining and I am glad, in a general sense, that a series that speaks so unabashedly for women’s liberation – even using force – has had such an effect on mass consciousness. At the same time, as a revolutionary socialist, I find the absence of any notion of collective struggle rather disturbing for a work of its nature as I do with storylines that put the main characters in the position of collaborating with “progressive” people in the Swedish state apparatus against its own security forces and the far right. Larsson was a revolutionary socialist as well at one point in his life, being a member of the Swedish section of the Fourth International.

I also don’t happen to think that as art, Millenium ever really rises much above the level of pulp – a fact due in no small part to the central character, Mikael Blomqvist. Blomqvist seems to me a male fantasy rendered in a very un-feminist way. Somewhat oddly, I seem to agree more with the hyper-sectarian World Socialist Website on this than my own organization. Even if they are a scab operation run by half-psychotic scum, broken clocks and so forth.

In a conversation I had with some comrades and other general left-leaning folks a while ago, I mentioned these things when the subject of Millennium came up. One comrade, whose company I’ve always cherished, had the most curious response; the gist of which was that Lisbeth Salander’s lovingly described vigilantism had a progressive purpose because in the context of the books she stood in for the working class. I found it hard to formulate a response to this.

But I digress. The other axis of our chart is quality in the most general sense. Obviously the judgment of quality is a very subjective affair, the reasons for which I’m not very interested in. We can get around this by dealing in terms of works whose quality or appeal is generally recognized, which I’ll get to in a second.

Laying emphasis on the axis of quality over the axis of politics also leads in some strange directions. The most popular one we are very familiar with. Something like this: I like x even though x is reactionary, rightwing, reinforces power relationships of class/gender/race-nation-ethnicity. Obviously this can be a legitimate response to the distorting impact of relying overly much on the political axis. But I would argue its effect is just as distorting.

To return to the example of Tolkien, I have heard generally left-wing people absolutely refuse to consider the reactionary attitudes to women and non-Europeans in The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien was on the record about this: “they [orcs] are (or were) squat, broad, flat-nosed, sallow-skinned, with wide mouths and slant eyes; in fact degraded and repulsive versions of the (to Europeans) least lovely Mongol-types.” (It’s less often recognized that the dwarves are in part an equally racist caricature: they represent the Jews, who in Tolkien’s mind had an irrational love for gold, spoke their own languages and never really tried to fit in with the larger society around them.)

There may be hardly any women and it’s said that orcs may represent a more than vaguely Sino-phobic caricature but, why should that detract from our appreciation of it as a text? I think to argue this is to place a barrier in between ourselves and a true appreciation of Tolkein’s universe – which surely requires us to appreciate the mind of the creator and how it was affected by the surrounding class society with all its prejudices. To say this doesn’t involve the intentional fallacy, the application of which postmodernism has [u3] utilized to turn a useful piece of advice into its opposite.

What I’m arguing for in short is a holistic revolutionary socialist approach to art and culture. This is very much in the tradition of literary revolutionaries – Marx, Engels, Trotsky, Lukács, Brecht and Benjamin – who argued that the understanding of the conditions of production for any work of art was key to the understanding of the work of art itself. The political critique can be allowed to trump the critique of quality, or vice versa in this form of inquiry.

I’ve been overusing it lately, but I think the phrase “concrete analysis of concrete conditions” put forward by Lukács is really the secret of the Marxist method. The method includes all criticism but specifically for us, cultural criticism. So we have – the concrete analysis of concrete art.

One example I find incredibly useful, raised by China in his talk, is that of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. This is a wonderful book in my opinion, among any reasonable “top ten” of English-language literature in the modern era. However, Conrad explicitly intended his book as a plea for the “enlightened colonialism” of Britain, his adopted homeland (a point of view given voice repeatedly by Marlowe, the narrator), as against the supposedly more savage rule of King Leopold in the Belgian Congo.

Heart of Darkness is a work of such importance that using just one axis of critique I have outlined will not suffice. This has not stopped the literary and political left, however, from praising it as a work of literature while pointing to the supposedly limiting conditions of its imperialist politics (a critique advanced much by Chinua Achebe and other postcolonial African writers).

What China says about Heart of Darkness is that we should consider another avenue of critique. As the novella is a product of a colonial culture, what were the things that made it compelling in a society whose common sense regarded colonialism as a positive? In other words, Heart of Darkness may be compelling precisely because of its reactionary stand on colonialism. Form and function are, after all, united in a dialectical whole – which should get us to consider that Conrad’s book is compelling for the same reasons it is politically reactionary.

The water gets even more muddied if we take a closer look. At the same time that Conrad’s implied author is a proponent of colonialism, the characters and events in his own novel revolt against this view. Much has been speculated about the character of Mr. Kurtz, whose brilliance is told of from the beginning of the book, but when he appears, he barely says anything. I refer most of all to a line that is as famous as it is misunderstood: “The horror… the horror!” Part of the misunderstanding is of course based on Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, which seems to adapt the novel only in how Coppola misinterprets every part of it in the most systematic way one could imagine.

Now, as someone who loves Heart of Darkness, what I understood Kurtz means by “the horror” is not the horror of the darkness and barbarity he has been reduced to in the “savage” Congo – it is his realization that the comfortable, sedentary bourgeois way of life he enjoyed back in Europe is based on the systematic acts of exploitation and barbarism he engaged in as a colonial official in Africa. Surely one could not ask for a better literary condemnation of the system of imperialism, even if it is only implied.

Lukács was noted for his view that literature was only progressive if it exposed the dynamics of the whole society – the capitalist system as an internally mediated totality. Based on this notion, he tended to reject all forms of literary expression outside realism as reactionary. His view has often been reduced to the point of caricature. It is never noted, for example, that in the context of the struggle against fascism, Lukács’ view was linked to an attempt to salvage Enlightenment rationalism – something that he thought for better or worse was part of the Marxist heritage. Nevertheless, his views did incline to a certain purism which was not helped by his embrace of Stalinism – see for example his incredibly unsubtle denunciations of writers of such stature as Franz Kafka, Virginia Woolf and Rabindranath Tagore.

I don’t mean to comment on the long-running debate between Lukács and Brecht – I’m not sure I fully understand it although Brecht’s notions seem closer to my own impressions of the truth. But Lukács’ notion that we can judge art in terms of how it exposes the totality of social relations strikes me as a useful guideline, or at least a reminder of what good art can accomplish. It is also a useful corollary of Marx’s, and especially Engels’ own views on art – that good political art does not accomplish its point through propagandizing, but through subtle subversion of the existing social relations. This incredibly hard goal has only been reached by a very few political authors, among whom I might mention China himself.

Another way of putting the case is the following: We would never have to think about art in a nuanced political way if there were no good fascist artists, This is, of course, not the case. To restrict ourselves to literature alone, there have been some wonderful authors of the far right. Some of these, off the top of my head, are Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, Knut Hamsun, Gabriel D’Annunzio and Yukio Mishima.

Another way of putting the case is the following: We would never have to think about art in a nuanced political way if there were no good fascist artists, This is, of course, not the case. To restrict ourselves to literature alone, there have been some wonderful authors of the far right. Some of these, off the top of my head, are Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, Knut Hamsun, Gabriel D’Annunzio and Yukio Mishima.

To describe their art as a fundamentally political intervention in society – that is, political in a fundamental sense – should not stop us from appreciating what they do, and especially how they do it. Trotsky’s essay on Céline pointed to the contradictions inherent in the author’s worldview as shown in his first novel, Journey to the End of the Night. Trotsky concluded that the disgust with the hypocrisy and barbarism of bourgeois society that drips from every page of Journey could go one of two ways: Céline would either see the light of revolution, or he would adapt himself to the night. We know in retrospect which way this played out.

The question of fascist art might be a bit of a heavy example to use. So I will end with considering a different one: that of cultural kitsch, especially in its reaction to the war on terror. I mean primarily Homeland, which I seem to keep coming back to in my writing.

From my perspective, Homeland is an enjoyable show. It is not great art, but so little TV is. TV is functional as it is meant to entertain and explain at a very basic level. This, Homeland does admirably. I see it as very compelling and interesting even as I recognize that what it does is to reinforce and justify the intervention of the US government into foreign countries and its repression of native Arab and Muslim communities; it’s fundamentally racist and imperialist.

Unfortunately if you praise the merits of a show in this genre among socialists, in my experience, you tend to get accused of sharing some of its values or at least ignoring them. This is very different from what I’m trying to do. At a fundamental level, most cultural products of the Homeland variety share the same values but surely we should have a bit more to say about them than “that’s racist” or “that’s imperialist”? Shouldn’t these declarations (perfectly true, mind) be followed by some sort of exploration of how racism, imperialism, etc are perpetuated?

This brings up something else, very important I think, in China’s guidelines: The idea of art as a “guilty pleasure”. He says that whether the guilt comes from bad politics or poor quality, it is fundamentally dishonest. There is no real guilt in pleasure, except the kind that is staged and performative in the declaration of a “guilty pleasure.”

It’s related to the tendency among people – not just socialists – to take something amiss when someone else disagrees on cultural and artistic preferences. All too quickly, a civil discussion on x cultural product can turn into something along the lines of “You don’t like x? You bastard!” (or, of course, the reverse, which I have experienced). Something which, as China says all too rightly, is an expression of commodity fetishism – to prove his point, many of us hissed during his talk when he mentioned he dislikes The Wire.

One caution I have here is against a sort of relativism that China’s critique implies. As an example, I think there are some really great left-wing movies out there: Reds, Matewan, Norma Rae all come to mind. Would it be a complete distraction to believe that some of their appeal comes from the very clear way in which they propose a politics of liberation? I think this would be to miss the point in a pretty major way. The reverse of this is, as China mentions, that if all your favorite books are written by fascist authors, it likely says something about your worldview.

I don’t mean all this to be systematic, much less advisory in any way. I would only offer my hope for a deeper and more systematic critique of all art on an intelligent political basis. Conclusions can be drawn as the result of further conversation.

“Toward a Holistic Revolutionary Critique of Art” originally appeared in Red Wedge Magazine and Strike #3 . More essays by Bill Crane are available on his blog http://thatfaintlight.wordpress.com/

Bill Crane is a socialist writer and activist living in London, UK. He has been active in the movements for housing rights, women’s rights and reproductive justice, and a variety of other issues. A member of the International Socialist Organization, he has maintained the blog That Faint Light (thatfaintlight.wordpress.com) for several years, where his commentary on literature, politics, history and Marxist theory has appeared. His other writings have been published at Socialist Worker (socialistworker.org), Red Wedge Magazine, ZNet, and elsewhere. A recent graduate of Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, NY, he feels most at home either reading, messing up articles on Wikipedia, or discussing arcane Marxist theory over a beer.

The Fix 10/03/2013

Another (late) edition of The Fix is bringing you another round of nuggets from the world wide web.

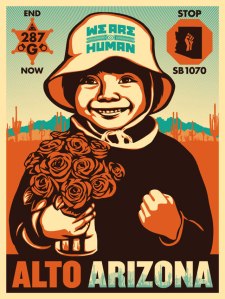

Elyveth: Some of us forget how big a role technology and social media play in organizing and getting information to the people. This article looks specifically at CultureStrike and how designers use technology strategically to get their messages out quickly and virally all over the world. They conduct silkscreening workshops to teach young people how to cheaply produce a run of posters for a rally or demonstration. Using social media, they allow downloading of their posters for quick distribution, and that’s just scrapping the surface.

Elyveth: Some of us forget how big a role technology and social media play in organizing and getting information to the people. This article looks specifically at CultureStrike and how designers use technology strategically to get their messages out quickly and virally all over the world. They conduct silkscreening workshops to teach young people how to cheaply produce a run of posters for a rally or demonstration. Using social media, they allow downloading of their posters for quick distribution, and that’s just scrapping the surface.

Raul: This ain’t exactly cutting edge, but I came across this radio station, KEXP, out of Seattle that regularly holds these short in-studio performances with a wide array of alternative and indie artists. The setting is nice and intimate, the interviews are informative and some of the artists seem to really get into it. Favorites include performances from Grimes, Neon Indian and Beach Fossils. I picked this mostly because we’re getting our own radio show (woo!) and I would love to see us get to this point one day.

Raul: This ain’t exactly cutting edge, but I came across this radio station, KEXP, out of Seattle that regularly holds these short in-studio performances with a wide array of alternative and indie artists. The setting is nice and intimate, the interviews are informative and some of the artists seem to really get into it. Favorites include performances from Grimes, Neon Indian and Beach Fossils. I picked this mostly because we’re getting our own radio show (woo!) and I would love to see us get to this point one day.

Mike: Street art has played a continuous role in the development of the revolutions of the Arab Spring that began a couple of years ago. As people took to the streets in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and other places to demonstrate against repressive regimes, street artists amplified the voices of those struggles. In Syria, revolutionaries have been engaged in one of the most protracted, bloodiest fights in the region. And, artists in Syria have participated in that battle from the beginning.

Mike: Street art has played a continuous role in the development of the revolutions of the Arab Spring that began a couple of years ago. As people took to the streets in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and other places to demonstrate against repressive regimes, street artists amplified the voices of those struggles. In Syria, revolutionaries have been engaged in one of the most protracted, bloodiest fights in the region. And, artists in Syria have participated in that battle from the beginning.

In this piece Vice talks with Syrian street artist, Tarek Algorhani, about the role his work plays, facing down the Assad regime with art, and the costs of the Syrian revolution for the people and for artists.

Beatriz: Blam! “Knowing Where Youre Gadgets Come From” –Hyperallergic

“So much of the electronics we use are built on the backs of child soldiers and millions of dead, a war the world ignores but has killed more people so far than World War II.”